“Children of abuse are asked by their lives to go back, to face yet again their abusers and all of those places tainted by the memories of that past they endured, that cloud of constant fear, the threats and insults they survived. It is weighty work, and requires breathing through memory triggered panic attacks that appear from out of nowhere…”

Journal Entry: July 1, 1972

My Heavenly Father,

A deep sense of confusion dwells in me, God. I can only turn to you, but sometimes (most of the time), I feel incapable of reaching you. Why, my Lord? What reason have I to distrust you? Have you not answered all of my prayers? Why is it so easy for me to discredit these answers and forget your guidance in the past?

My heart is deeply troubled.

What can I do but sit silently and wait for this trial to be over?Memphis, Tennessee: Summer 1972

Landing on the airport’s new runway completed an unexpected circle in my life. Just a few years before, the earth beneath it had been loamy and lush, immensely comforting, home to a vast grove of ancient, mystical trees. I had lain safe there, held within the forest’s shady embrace for a hundred afternoons, concealed and content, lost to the world beyond. I had wandered countless hours beneath its leafy canopy, exploring its mysteries and my own puzzled heart, hidden from Mom, able to stretch out and breathe, able to play, able to daydream.

There within that ancient, wooded sanctuary, boyish curiosity and a restless sense of adventure had compelled me, again and again to climb into the highest reaches of its soaring maples and oaks, and sometimes swing down between their lower branches and trunks like Tarzan; woody vines that stained my hands green and black, and occasionally broke, mid-flight. “Whuumpp!”

For three years the cathedral of that forest had been my secret delight, a place I went alone and kept for myself, save for the one time I took my little sister, Cyndi who swore an oath to never breathe a word, and then, to my surprise, didn’t.

I floated there, unseen in summer, weightless and suspended within humid pools of dappled sunlight, watching photons filter downward through emerald leaves and dance with motes of dust. I wandered there, lost in awe, studying ornate spider webs and recording elusive flashes of color and sound on lined pages tucked into the back of my bird book, cardinals, indigo buntings, scarlet tanagers, brown thrashers, mockingbirds, oven birds, red-headed woodpeckers, blue jays.

When autumn came, I buried myself in mountains of rustling gold, breathing the rich, decaying smells of fallen leaves deep into my nostrils and soul, tasting the weight of cool, humid air and sometimes daydreaming myself to sleep.

In springtime I tracked shy, Pileated Woodpeckers among giant hardwoods, vectoring in on their eerie calls, selectively focusing out everything else. Suddenly, the rat-a-tat-tat of a powerful bill against yielding wood; brief, binoculared glimpses of red, black and grey, audacious, feathered poems in bold, undulating flights between trees high in the canopy.

When they cut my towering friends into logs and tore the earth with their giant machines I mourned the destruction as perhaps only a child can. Over the years those woods had become a friend to me. They had taught and fed me, hidden and comforted me. I was not prepared to watch them die.

Within a few short weeks all evidence of my magical forest disappeared.

Numb with loss, I walked my bicycle along the busy perimeter road daily, looking on in exile as huge earth movers scraped and rearranged the land. I sat in tall grass along the ditch curating hatreds for people I'd never met, asking questions no one would answer:

“Why did you have to build the new runway here?”

“Where are all the birds and squirrels that once lived here and how will they now raise their young?”

“How many did you stupid bastards kill?”

Those once-wooded acres beneath the new runway had been my Sherwood Forest, my sanctuary at the edge of a world nearly black at times with confusion. No trails. No roads. I had never, once seen a grownup within its wooded grasp. Just ancient forest, dark and thick, and full of wonders; heaven for a kid on the run.

"Captain Richardson has just notified us from the flight deck that we are cleared for landing.” a uniformed woman’s voice split the air above me suddenly. She looked disarmingly young and fresh standing there in the aisle but had already mastered that insincere, sing-song all stewardesses seem doomed to attain. “In a few moments we will be turning west to begin our final approach."

I liked her hands; perfect pink nails; lipstick to match. Her polished lips were full and animated, sexy even; soup coolers. I wondered what they’d be like to kiss.

"Please make sure that your seat belts are securely fastened,” her lips practically brushed the microphone as she spoke, “ ...that your tray tables are stowed and that your seat backs are in their full, upright positions. We will be landing in Memphis shortly."

Out my window, I could see the lay of familiar lands streaking past; childhood haunts staring back at me. Just one short year away and I had become a stranger here. New houses encircled the once-wooded lake where Melvin and I had fished for bluegills with bacon and worms, and taught ourselves to fool bass with poppers in the rain; where I had learned to smoke unfiltered, Pall Malls and tossed twitching, hook-gored, little bluegills into the water near the lairs of water moccasins to tempt and catch them. Twice I actually hooked one of these fearful serpents, then reeled it in and hacked its gagging head from its writhing body for sport.

Newsflash: Boy with hatchet meets deadly viper with fangs; boy wins.

In the distance I could make out the block where our old house still stood and see its grey-shingled roof. I wondered if my steel-tipped darts were still up there in the rain gutter or our beloved, cat, Baby’s bones, still buried at the foot of the sweet gum tree in back.

Nineteen-seventy-nine Nellie Road, a four bedroom, three bath, tri-level with a concrete patio and two-car garage; mid-century purgatory …that nightmarish place between Heaven and Hell where only the prayers of others can effect your escape. For all those nights you did pray for us, Grandma, I will always be grateful!

I wondered if some farmer had named our street for his favorite horse. Whoa Nellie! Maybe a racist farmer. We did live in Whitehaven, after all. Fitting irony that the last time I drove through the old neighborhood its population was almost entirely black, and Whitehaven, just a clueless, worn out name.

But Mom doesn't live there any more.

The runway appeared below us and I flashed back to lonely nights when I would ride my bike to the airport in darkness, sneaking out onto all those miles of new, deserted concrete; dump trucks and graders, earth movers parked atop them like so much litter.

My beloved forest had disappeared and this was all that was left.

I’d thought about putting sand in their fuel tanks but knew it wouldn't bring back my trees. Besides, with the way my luck was going, I’d almost certainly get caught? My life was messy enough already.

I peddled and coasted, alone and free under cover of darkness, the entire runway to myself; two and a half miles of smooth, featureless concrete. I rolled along, popping wheelies and pedalling without hands for hours, studying the moon, its upward climb through silvery clouds and across the black sky, while noisy jets took off and landed in the distance, and frogs and nighthawks sang to me.

On my last night in Memphis I was relieved when Mom finally started dressing to go out with friends. I’d been afraid she’d stay home in some pathetic, last ditch effort to play the good mother, told myself, over and over that I didn't care if I ever saw her again, that I hoped like hell she'd leave. When she did, finally, I waited the usual ten minutes to make sure she hadn't forgotten something, then grabbed my last half-pack of Marlboros from under my mattress and headed toward the airport. I wanted to say my good-byes alone, riding up and down that new runway, chain-smoking. It was to be my last night of freedom; final, silent rebellion.

Weaving cat-like between graders and backhoes, inhaling bitter smoke and jet fumes, I felt distant and cool, put upon, like Steve McQueen. I pictured myself alone in the world. Invisible. Unappreciated. Misunderstood.

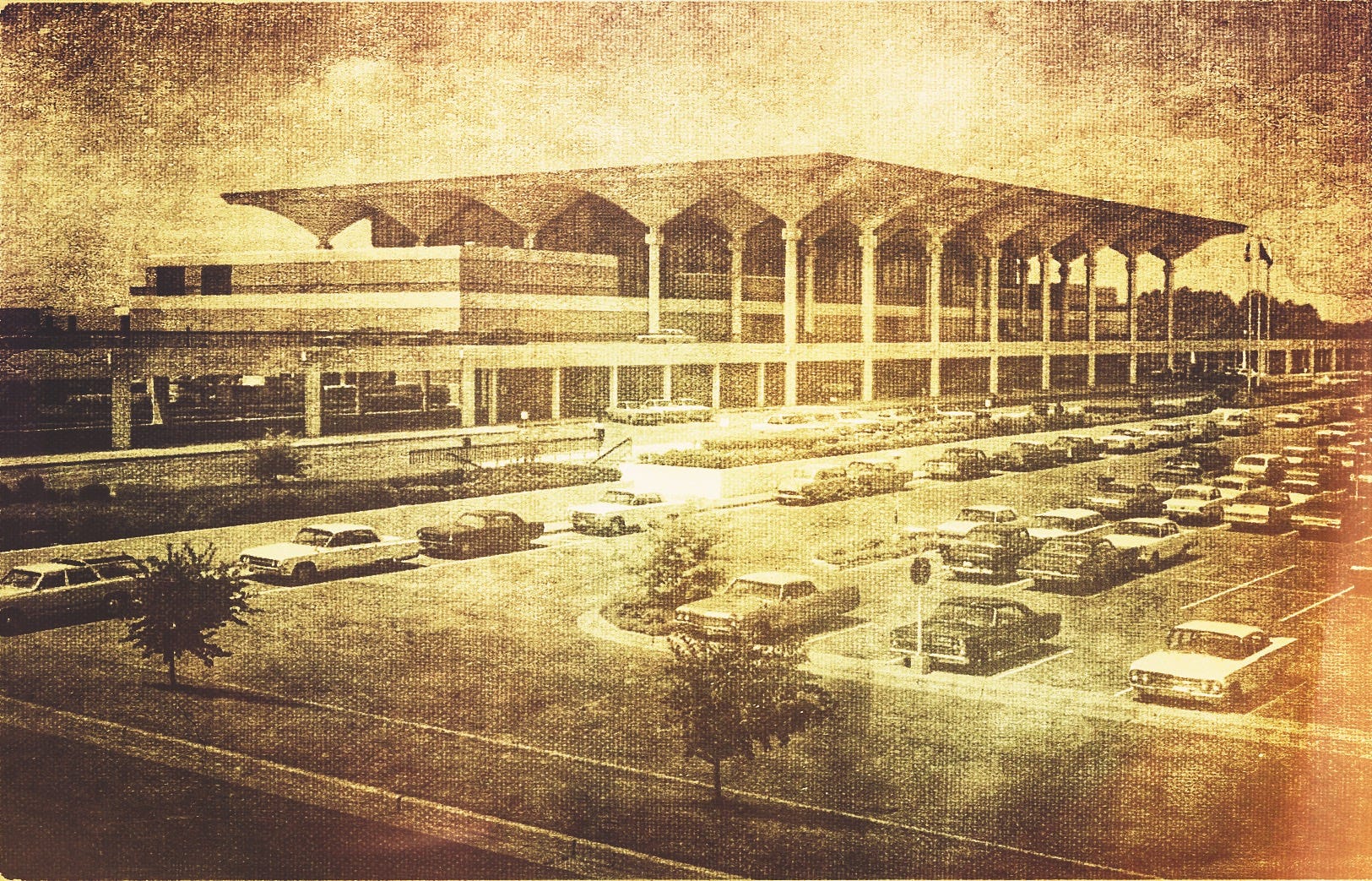

The terminal building, like a giant tray of champagne glasses in the distance was lit up for business while cars and airplanes pulled up and away on opposite sides in endless succession. Tomorrow morning it would be my turn. I was leaving Memphis forever.

"I can't fucking control you any more!" Mom screamed one night, as if she had just in that moment understood. "So you’re out’a here, Mr. Smartass! Maybe your goddamn father can do something with you.”

“And if he can't," her words pummeled and sliced in cruel afterthought until I wanted to scream too, "I know they'll whip your ass into shape at that church school. Oh yeah, those Adventists will take a cocky little smartass like you down a peg or two in no time.” She turned then and stomped out of my room.

“Bet on it!" she shouted, slamming the door behind her.

Thoughts of Seventh-Day-Adventist church school terrified me far more than those bullies I knew would be awaiting me if I stayed and attended Hillcrest High, more than almost anything. Smarmy Christian teachers. Endless Bible classes. Girls that didn't put out! Vege-meat! Mom was certainly savvy enough to know all this since she'd been planting her own visions of church school's worst horrors in my head for years. With her able taunting, those last few months in Memphis dragged on forever. I was a guilty man on death row awaiting my inevitable doom. Dear woman, she never once missed a chance to rattle my cage.

We were floating then, magically, mere feet above the blur of pavement. I was surprised how quickly black skid marks had built up on the new concrete, since the runway had still seemed months from opening the last time I had ridden my bike the length of it just a year before, christened it with one, last, defiant piss, believing with all my heart I’d never be back.

When our wheels finally touched, I saw the puff of smoke and felt the plane hunker down and shudder. Captain Richardson asserted himself quickly then, hitting the reverse thrusters and brakes simultaneously. My already queasy stomach lurched and rolled. Scenes outside slowed quickly.

Across Airways Boulevard I could see Grace Baptist Church and its failing asphalt parking lot where I had practiced skidding my bike sideways with Tripp and BooBoo on hot afternoons. Mom made us dress up and attend Sunday services there one Easter, an ill-fated decision that cost her a barrage of hard looks and us kids, a morning of shame.

Could it have been her jet-black, ‘Marge Simpson’ beehive? Or maybe it was the inch-thick, Jezebel eye make-up, tweezed and painted eyebrows, and go-go boots? Or perhaps her short, tight black skirt? What precisely were you expecting here, Mother, dear?

Just as it had been on other, occasional ‘visitor in somebody else's church’ experiences, there were a handful of over-sweet, 'God loves you' smiles and a few clammy, Christian greetings. But by the time anyone seeming even the least bit sincere had tried to be nice the damage had already been done. I swore I’d never step foot in that place again and pocketed the offering money Mom had handed each of us in the car. No way was I dropping a perfectly good, 1942 Mercury Head dime into that fucking, green, felt-lined plate.

I tried to distract myself, imagining that God would surely despise this insincere congregation as much as I did and send angels to help Mom to see the light so we could leave early. And then I heard it:

"Oh my Lord in heaven," a prim, hard-mouthed woman in her fifties whispered inelegantly as we walked past in the foyer. "Why, she's got some nerve coming in here dressed like that!"

I glared at her in hateful retort but doubt the bitch noticed.

"Easssster!" her apple-cheeked companion hissed then in thorny response, "...prickssss at guilty consssciencesssss every year and they show up here in drovesss. Blesssssed are thosssse who endure, sister,…" she snarked, her lisping voice drawling in snakelike parody until it dissolved into the chattering crowd behind us.

"Stupid hags!" I muttered to no one in particular, dutifully following Mom toward the sanctuary door, gut-punched and embarrassed by seeing myself through their eyes, entertaining bloody Easter thoughts of my own.

Earlier, during Sunday School class downstairs my sisters and I had speculated that Mom's conscience must really be bothering her to endure this sort of humiliation. Why wasn’t she more indignant, we wondered? All those hostile looks and whispers; it was as if our mother had become, temporarily blind and immune. We never did figure out what was eating her that day.

As the lumbering Convair turned off the runway I could see down Airways Boulevard to the hallowed little intersection where Hatch's corner store had once stood. Years before, we had been regulars in that dingy old store, collecting discarded pop bottles along the roadway and hoarding small change to trade for penny candies, popsicles and cold drinks. After walking or riding our bikes nearly a mile in summer heat, Hatch’s swamp-cooler air conditioning and the colorful displays of jawbreakers and bubble gum were part of our reward. We spent dozens hours within its walls, agonizing; fudgesicle or soda pop? Fudgescicle or pop? And if soda, would it be a reassuring, twelve-ounce Grape Nehi or a biting, sixteen-ounce RC Cola that could fuel a barrage of tearful belches and put some hair on your chest?

Mr. Hatch was a friendly old man with a generous face and gray, rheumy eyes. He liked children, or at least he liked us, and in a world of impersonal adults who scarcely noticed kids we absolutely considered polite, stoop-shouldered, old Mr. Hatch to be both our friend and our business mentor.

One summer, we decided to open a popsicle stand in front of our house and went to Mr. Hatch for supplies. Businessman that he was, he encouraged us to sell candy and gum as well as our ‘secret recipe,’ popsicles (Mom had showed us how to mix Jell-O and Kool-Aid together for a frozen popsicle you couldn't suck the juice out of). Then, he offered us volume discounts that would help us turn a profit. He had run such a wonderful little store. But it had been gone for more than a year by the time I left Memphis, overtaxed and then annexed, it too, killed for that goddamn runway.

The airplane seemed to creep those last several feet to the gate and for once the tactic pleased me. I studied the familiar lines of the terminal building once again while we inched forward. Nothing about its strange facade had changed that I could see. Memphis International Airport still looked pretty much like a gigantic tray of champagne glasses and again I wondered why. Was the architect thirsty when he designed it? Not likely. Hung over? More likely. I’d always doubted the design was symbolic; Memphis just wasn't a champagne kind of town. A couple of highball glasses and a decanter would have been more appropriate if booze was the theme. Or maybe a six pack of Bud, or better yet, a brown paper bag.

I had ridden my bike to the airport dozens of times as a kid, weaving through churning traffic and occasional taxis. It never occurred to me at the time that I was doing anything particularly dangerous. When I arrived at the terminal I would chain my bike to a newspaper box, outside and then sit for hours within air-conditioned comfort, watching airplanes and people come in and leave.

The airport was exciting, a place where you could watch a hundred adventures an hour begin or end, and all from a comfortable seat. But more important, it was also a place to hide from Mom before she left for work and kill time, a thing I felt compelled to do quite often.

Inside the terminal’s airy expanse, or outside on its observation deck I invented romantic stories as people ran squealing to hug one another or sobbed into hankies at the gate; entire lives formulated from momentary glimpses, nearly always more promising than my own.

Now, here I was, back at this same airport; my turn to meet someone I was supposed to be happy to see. Yet another completed circle, unwanted, unexpected, unknown.

I was not at all sure how I felt, or should feel.

When the plane finally stopped, a muffled chime rang twice and the seatbelt sign blinked off. Then all around me the metallic click of seatbelts being released and everyone pushing into the aisle like a herd of anxious cows. Everyone but me.

My heart leapt up into my throat and I felt like crying. I was terrified to get off that plane.

© David E. Perry. All rights reserved.

When I was fifteen I lived in a boarding house in Mississippi during the summer and worked, seventy and more hours each week …on a catfish farm where I earned just a dollar an hour. The work was honest, if the circumstances surrounding it were not. My mother was dating the fish farm’s married owner. His wife wrote and signed my paychecks every week. He knew I knew. I knew he knew. I was both liability and oddity, a hard worker trying like hell to be worthy of my paycheck rather than the nuisance brat of some fancy piece of tail.

It was complicated.

Thanks for the great images and emotions of your youth which resonated deeply (how do we survive those tender years - there must be a higher power at work in some of us, maybe most of us, that compels us forward day by day).

A heck of a narrative David, clearly painful to you, but enjoyed it a bunch! Then I'm going whaaat! Denied...? Lol!