Comfrey, Mississippi: Summer, 1972

I rented a sparsely furnished, single room from Mrs. Jimmy Simms and her younger sister, Bessie. Together, they owned a large, two-story home at the south end of Main Street, the only house in Comfrey that took in boarders.

Mrs. Simms was widowed, a cook at the local high school; Aunt Bessie, a white-haired old maid who’d invested much of her life caring for Buddy, Mrs. Simms’ severely retarded only child. When I first met these sisters Buddy was nearly fifty years old and still their shared baby.

I liked the look of their place immediately. The picket-fenced front yard was carefully manicured, Bermuda grass cut short, vigorous rose bushes blooming in profusion and heavenly honeysuckle, vining golden-green along the porch.

Several feet from a root-buckled sidewalk that lead to the front porch stood the impressive magnolia tree that had broken it, perhaps forty feet tall, waxy leaves and cream-colored blossoms promising evening breezes so thick and balmy that some nights the air would seem nearly pregnant with their fragrant dew.

Many of the larger houses in Comfrey were built on a colonial theme, abrupt, brick and clapboard structures fronted with fluted wooden columns supporting absolutely nothing. The old sisters’ home was far less auspicious; a wide, screened-in porch graced its white, plank front, disdaining useless columns and other ornamentation altogether. Here, residents and company could sit comfortably during warm evenings, grateful and mosquito free, sipping iced tea, inhaling the perfumed air and watching fireflies write silent poems as they sortied and signaled, punctuating the deepening dark.

I had learned of Mrs. Simms and her sister that first morning, shortly after I’d arrived at the fish farm. Mom had dropped me off at the hatchery rather hurriedly with just my suitcase, a sleeping bag, a twenty dollar bill and no clear idea of where I would spend the night. She had explained rather delicately on the drive down from Memphis that she didn’t want to create any problems for Bull Jackson or run into his wife, so when she pulled up to the hatchery she gave me a quick, apprehensive hug, wished me luck and was gone. After nervous introductions inside, Bone calmly offered up that a couple of elderly sisters in Comfrey regularly took on boarders, then sent me to town with Vernon to meet them. My work day would begin once my sleeping arrangements had been sorted out, he smiled.

Meeting the two sisters made a much larger impression on me than I had expected. Vernon had dismissed them as a couple of batty old gossips on the trip into town but I found them completely charming in that uniquely Southern manner; polite and very proper but without a shred of sophistication.

In the same moment I rang their bell Bessie and Mrs. Simms met me at the front door smiling effusively, as if they’d been standing just behind it waiting for my arrival (apparently Bone had called ahead). Moments later I found myself seated across from them in their cluttered front room, sipping sweet tea and answering questions.

So many questions.

And yet, quite early in this interview I already sensed that I was a puzzle they had decided to take in and solve. The two of them studied me carefully, analyzing the odd sound of my West Coast speech, my grooming and posture. More important than these, though were my answers; that seemed apparent. Again and again they laid out the next in an intricate maze of inquests, dropped it at my feet, then beckoned me to respond.

“Yes ma’am, my Daddy had taught previously at both Memphis State and Ole Miss, but he now teaches at a college out in Washington.” I explained.

“No ma’am, I haven’t been to the White House. We live in the state of Washington,” I said.

“Yes ma’am, that one way out there by Alaska.”

“No ma’am, my Momma still lives up in Memphis.” I tensed, hoping they wouldn't want to explore this area too deeply.

“Yes-um, divorced... uh-huh, many years ago. Back when I was in third grade,” I offered, relieved by the distance of time.

“Oh yes ma'am, Mr. Jackson and Mr. Hancock do seem like very fine men.” I fibbed. I’d never met 'Mr. Jackson, but I had seen pictures of him, one in particular with my mother sitting on his lap and smiling with those dreamy, ‘maybe this time’ eyes. It seemed clear to me that she, at least, thought he was quite fine.

“Well, yes ma’am, of course. I certainly am looking forward to working for them.” I said, beaming, without a shred of pretense.

“No ma’am, I’m only fifteen, but I assure you, I'm very responsible,” I sat up just a little straighter.

“Oh yes ma’am, a devout Christian." I smiled. "Yes ma'am, that I certainly am.”

Impressed sufficiently with my family background (both were comforted noticeably when they heard my Daddy had taught at Ole Miss), and reasonably certain of my employability as well (Bone’s phone call had taken care of that), their expressions grew softer, especially Aunt Bessie’s.

Hers was a face for a boy to get lost in, and from our first meeting that is exactly what I did. While Mrs. Simms’ shrill voice squawked and pummeled, demanding obedience and submission, Bessie sat mostly silent, smiling generously, feet modestly close together, hands folded neatly in her narrow, aproned lap. She was a pushover for polite young men, that much seemed plain.

Perhaps years of missed opportunities and longing had worked her heart close to the surface, I never did really learn. I only knew that morning that she was a lovely, gentle-souled old maid, as anyone from the South might have, for there was no proud ‘Mrs.’ at the front of her name. She was just plain, Aunt Bessie, not even encouraging the title ‘Miss’ anymore. Perhaps she had decided she was too old to keep announcing her eligibility, thus.

I bet she was once a real heartbreaker, I thought, studying her kind face while her elder sister droned and sputtered, for Bessie, absent even the smallest adornment was still a rare beauty, despite her advancing age. I pondered often, during my time with the sisters what tragedy had kept Bessie single. Perhaps she had been jilted or lost a lover to war, or sickness. But in the months I boarded in their house, she never did offer many clues to my riddle and I would never have dared ask.

Finally, when each of the customary, Southern formalities had been given their rightful due, the two sisters acknowledged what I had seen in their eyes half an hour before. They led me along a barren hallway and up creaking, black-stained stairs to one of three available bedrooms on the second floor. “This one,” Aunt Bessie leaned close to confide in a whisper, “has the nicest view.”

The room's sparse sleeping ensemble looked rather barren, a lumpy mattress lending sad shape to an ancient white bedspread which lay dejectedly between rickety head and footboards like a windswept sea in stasis. My future holds backaches, I thought, already missing my extra firm mattress back home.

The rest of the room pulled more slowly into focus; a single, south-facing window looking out into the heart of an enormous sweet gum whose branches cast the entire room of yellowing, blue-flowered wallpaper in pallid shades of green.

“Best view,” I pondered silently, “…wonder what the others are like?”

Beside the craggy bed stood a rickety table masquerading as a night stand, topped with an ancient fan and flanked by a wired-together, old, wooden chair. The only other article in the room was an antique chest of drawers standing lonely sentry beside a small, beadboard closet. Suspended high above the foot of the bed, a single bare bulb nested in an ancient, tarnished socket with a knotted pull cord, and beside that, amber flypaper spiraling downward, cracked at its edges and motionless, heavy from a lifetime of accretion: flies, moths, and mummified wasps.

“Cozy!” I thought sardonically, then turned to the sisters to accept.

Mrs. Simms immediately began reciting her terms: No smoking in the house and absolutely no drunkenness. Two towels and two wash cloths per week, and clean sheets every Saturday. I could come and go as I pleased through the back door, as long as I was quiet, and would need to take my meals at the cafe in town.

I would …need to ...ummm. What?

I tried desperately to act older and more nonchalant than I felt just then, but Bessie’s look told me she saw right through me. I coolly agreed to the terms, then haltingly, having drawn essential inspiration from her encouraging eyes and my own growing sense of doom, squeaked out one small request.

“Do you suppose, I mean, well, uhh Ma’ams, uhh, would it be at all possible for me to, well you know, uhh ...keep a small carton of milk for cereal and maybe some orange juice in your refrigerator?”

Dead silence.

“You know, for breakfast …in the mornings." I tried nervously to fill the uncomfortable abyss.

"I mean, uhh, from what Vernon, uhh, Mr. Rasmusson told me on the way into town just a bit ago I’ll need to be ready to leave for work at a quarter of five each morning and I don’t think, well, um, do you know if the cafe is even open that early? Well, no, I mean I don’t know for sure when it opens. Do you? I mean, is it?”

Mrs. Simms, sensing my weakness drew her beady, little, rodent eyes down to angry slits. Her hairy nostrils flared above an even hairier upper lip.

“Young man,” she barked, as if physically hurt, “I have nevahhhh allowed kitchen privileges to any renter in my entiahhh charmed life. Not even once. I suh-tainly do not intend to begin entertaining such foolishness now!”

Bessie stepped forward quickly, then, neither batting an eye nor missing a beat and granted me a one-week trial in the kitchen.

“Sister and I will be just fine with this,” she smiled, addressing the calming words toward me while staring down her older sibling, “long as ya’ll don’t take up too much space in the icebox. Why, we haven’t got much to spare!" she redoubled. "Of course you will also clean up any messes you make and you most certainly will not make any loud noises at such a frightful hour of the morning. Sister and I are rather light sleepers after all.”

“Thank you...” I whispered, head bowing in relief. But just as I was catching my breath, allayed that this storm cloud had passed, another appeared on the horizon: money.

Mrs. Simms explained that they would require the first week’s rent of fifteen dollars in advance, at which point I swallowed hard again, looked pleadingly again at Bessie and attempted to explain my temporary shortage of cash.

“Um, uhh, pardon, Mrs. Simms,” I said sheepishly, “Please! I’m terribly embarrassed to ask even one thing more, but I really don’t know what else to do. You see, I’ve only got the twenty dollars in my pocket (I quickly fished it out to make my point), that my momma gave me this morning when she let me off at the hatchery. And I, uhhh... well, I expect I’m gonna need every bit of that to eat and get along on till my first paycheck at the end of the week. Is there any way you might see fit, well, umm, I mean ...is there any way you could see fit for me to pay my rent for this week and then, say, another fifteen in advance, come Friday? I feel certain I’ll have earned more than enough by then.”

Bessie shot an arrow of a smile at her sister with amazing effect.

“Usually,” Mrs. Simms hissed, tossing a sarcastic look back at her younger sibling, “we require our rent in advance. But seein’s how we on such good terms with Mr. Jackson and Mr. Hancock, well, I guess ya’ll kin pay your rent at the end of the month ...if that’ll be convenient,” her hairy nostrils flared again.

I swallowed deeply, acting properly embarrassed for requiring such special consideration and gratefully agreed to her terms. Bessie beamed, first at her sister, then at me. My heart was none too wild about Mrs. Jimmy Simms in those first hours after meeting her, but I absolutely adored Aunt Bessie. Kind-hearted and obviously wise, she had already proven an invaluable ally to a kid who could really use one.

I reached out and shook both of their wrinkled hands, looking deep into their eyes and assuring them that I understood the extra mile they were going on my behalf, promising that they wouldn’t be sorry for trusting me. Then I joked that I’d better get back out to the fish farm to start earning my rent.

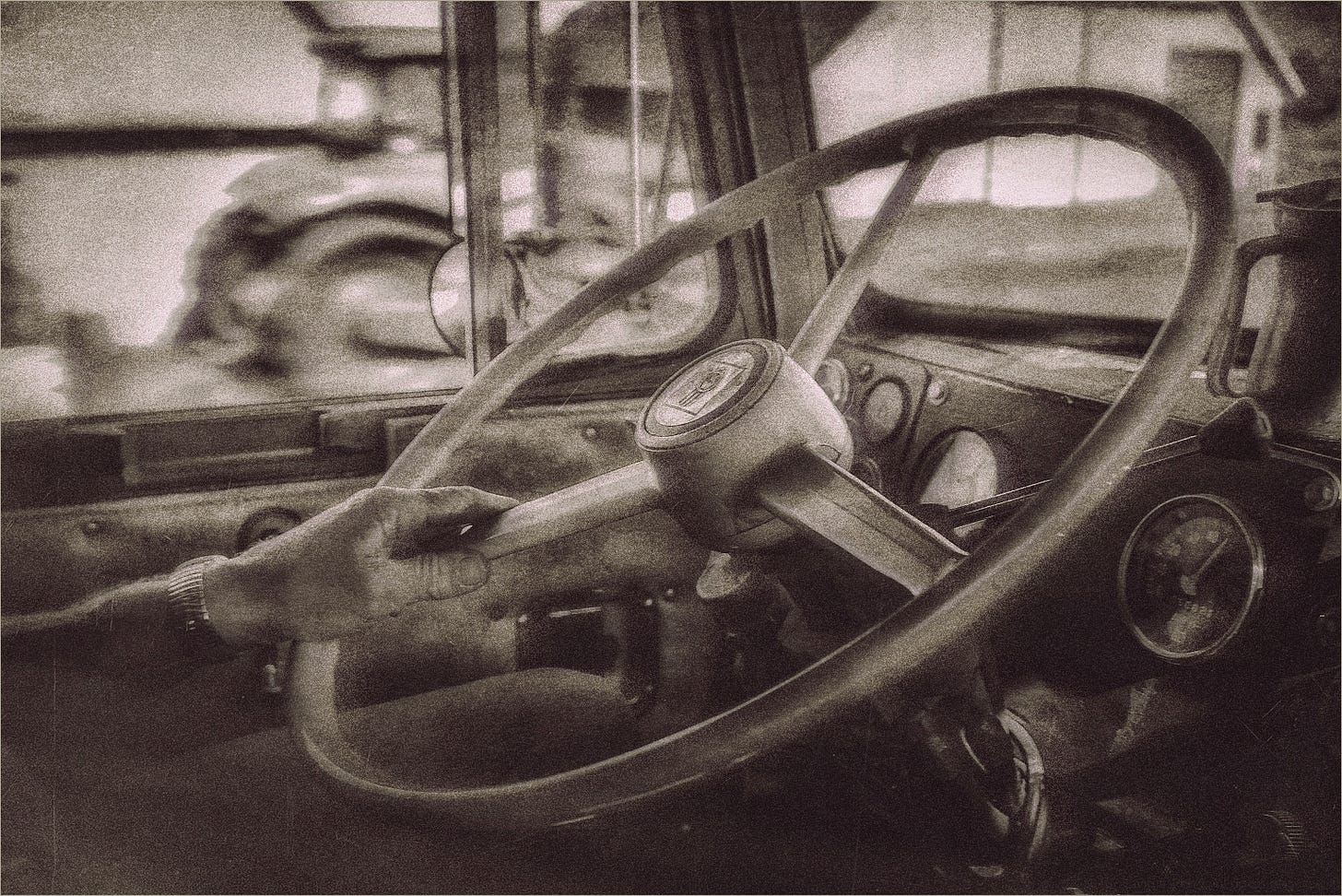

Back in the pickup Vernon was lost, head back, arm hanging out the window, floating through the clouds of some country singer’s broken-hearted lament. He perked up a bit when I opened the door and climbed in, but obviously had not the first clue to the immensity of the moment for me, which suited me just fine.

I had just rented a room in a boarding house, by god, just stepped up to the doorway of adulthood and given a hearty rap. Now I was headed back to the fish farm and deep into the swelter of summer, eager to earn my place and my worker's sparse wage.

Three months of hard labor awaited me in the backwaters of the Mississippi Delta, eleven terrible, fabulous, raw, lonely weeks.

I could not possibly have felt more alive.

©David E. Perry. All rights reserved.

When I was fifteen I lived in a boarding house in Mississippi during the summer and worked, seventy and more hours each week …on a catfish farm where I earned just a dollar an hour. The work was honest, if the circumstances surrounding it were not. My mother was dating the fish farm’s married owner. His wife wrote and signed my paychecks every week. He knew I knew. I knew he knew. I was both liability and oddity, a hard worker trying like hell to be worthy of my paycheck rather than the nuisance brat of some fancy piece of tail.

It was complicated.

Reminds me of To Kill a Mockingbird, those southern ways, those soft drawls come to mind again, those streets, those shaded afternoons and dark, dark nights, all never to be forgotten. It was both heaven and hell. I won't ever go back, but part of me never left.

This story is buzzing with summer coming-of-age heat. I ADORE your voice, your recalling of characters, and how moments build on one another to shape your becoming. Ray Bradbury reincarnated!