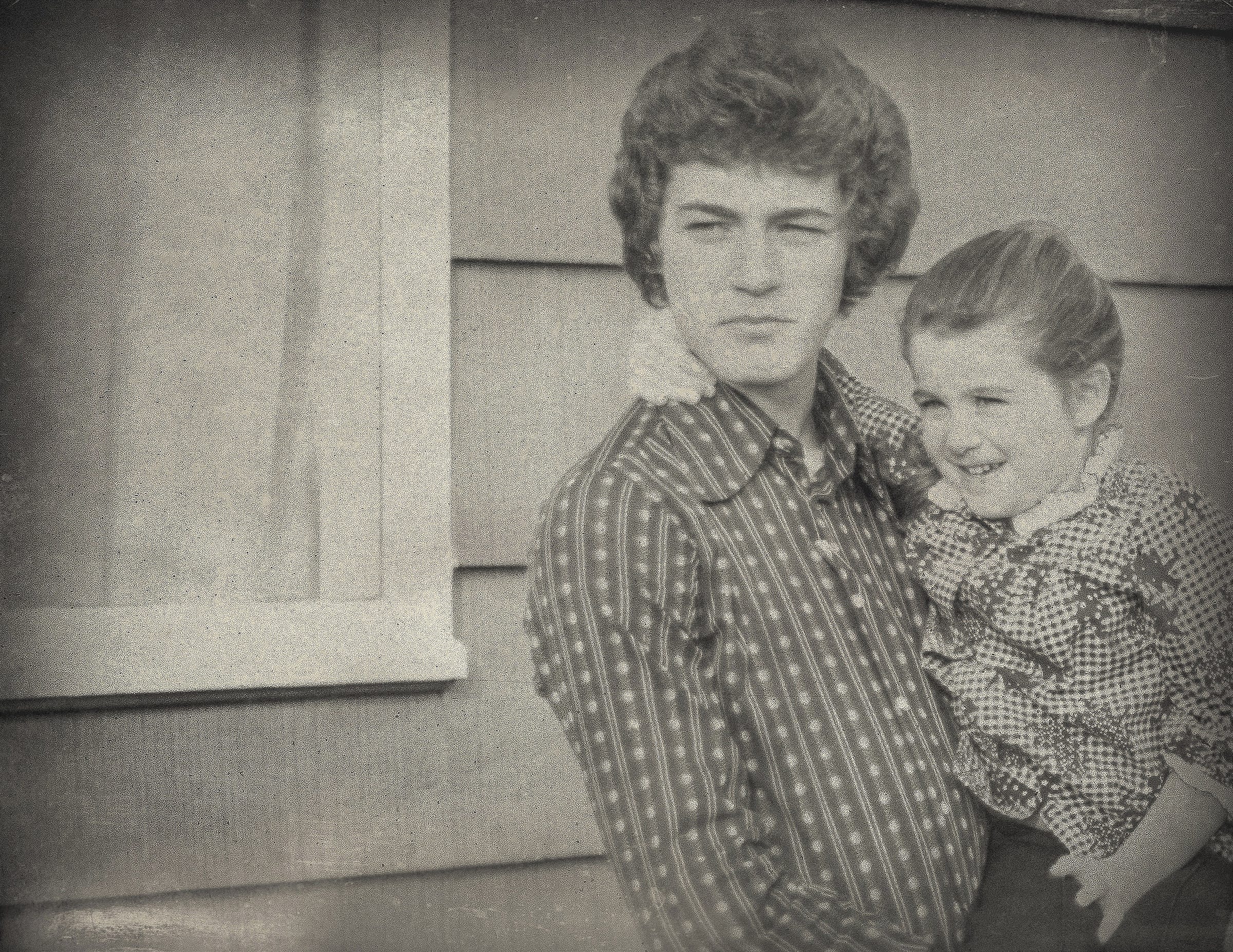

Memphis: Summer, 1972

Weekends were strange, dutiful times for me.

Confused. Unsettled. Bone weary.

Sad.

While the guys from work were almost certainly spending their weekends laughing and chasing women, plying them with barbecue, seventies dance moves and beer I felt mostly numb. My body was whipped and I was lonely. Heart weighed down, responsibilities still untended, sixty to eighty hours of hard labor already in the can.

I would have loved to be able to crash someplace warm and comforting for the weekend, preferrably with a swimming pool and cushioned recliners, but dutifully visited my mother up in Memphis instead, her single-story, brick and frame structure filled with artificially chilled air and tattered furniture, reeking chihuahua shit and eucalyptus leaves, layered with Emeraude perfume and stale cigarette smoke.

Mom generally wasn’t home much on weekends which was fine by me, but three-year-old Bonnie Boo was nearly always there. She was a delightful kid with enormous, kind eyes, a vivid imagination ...and a heart nearly too innocent to have come from our shared mother. Which may be why she scared me so; hoping for and seeing too much.

In me.

Acting as if I’d hung the damn moon …and done it just for her.

Bonnie once told a visitor that I could beat up Superman if I wanted to and said it with conviction. Such adoration and neediness were both delight and terror to me. I didn’t have the tools or the path to make them tenable.

When Bonnie was a tiny newborn I got up with her untold times in the middle of the night, changing diapers, warming bottles, whispering to her while we rocked back and forth in near darkness, while she worked her bottle and studied my sleepy, adoring eyes, affording Mom some badly needed rest. I learned much of the little I knew of love for a while there by loving her. I had helped care for her. Bathed her. Played with her. Marvelled at the miracle of her growth.

Watching her mind unfold was an unexpected gift, almost redeeming me some days from my worst, pissed-off, adolescent impulses. Perhaps, redeeming all of us just a little. From her first week in our lives Bonnie Boo was beautiful, good-natured and innocent ...all those things the rest of us had nearly forgotten we could be.

By the age of three she was even more magnetic and precocious than when I’d left the year before. And needy. Challenging in ways that proved nearly too heavy a lift for me. My questioning, adoring, little three year old sister was an intimidating responsibility.

I was a dumb, weary, teenage boy, endlessly confused.

During the week while I was down in Mississippi working on the fish farm, Bonnie was mostly Cyndi’s responsibility, which, of course was wildly unfair to both of them. Cyndi was a year younger than me. But then, for much of those weekends when I was ‘home,’ Bonnie became mine. Cyndi needed her breaks, too. You couldn’t blame her for that. My arrival home on weekends was all the permission she needed to put on some eye shadow, grab her not-so-secret, secret pack of Salem menthols and fly away with her girlfriends to laugh and decompress for a while.

Mom, consistent to her nature, never bothered to ask or even question who would watch Bonnie while she went out drinking and catting around, she simply knew that it would be done. So while Cyndi hung out with friends and found ways to unwind, I stayed home, did my week's worth of grimy, smelly, fish farm laundry while reading story books and playing games, and talking (though mostly listening), to chatty, little Miss Bonnie.

And sometimes we busied ourselves in the kitchen.

Chocolate chip cookies were Bonnie’s favorite. Nestle’s Toll House recipe, warm from the oven. They were a gentle, sweet ritual my paternal grandmother had taught me and my sisters when we were little, patiently re-enacting it for us, complete with ‘tester’ sample cookies each time we visited her reassuring little war-box home in Central Oregon. On weekends I carefully passed this ritual on to my baby sister, a kid who had no paternal grandmother to dote on her, who had no paternal anything, really ...except for passed-along genetics and an impending sense of loss.

Baking cookies with Bonnie was a manageable opportunity, a chance to be the sort of big brother I would have liked to have had myself, and hopefully the sort of friend my grandmother was to me. Chocolate morsels and quiet time, nurturing for a little sister who seemed trapped, wandering through life in a sort of hell that, really, was all she’d ever known.

Since Bonnie had never experienced anything different or better, I naively assumed that the constant swirl of uncertainty and squalor she lived in couldn’t feel so much like a trap to her, nor would she sense any great loss. These things were just her normal, I reasoned. They were all she’d ever known. Debbie, Cyndi and I remembered much, much better times and so each of us felt trapped and cheated, again and again by Mom’s choices. We had fallen so far. We remembered so much better.

I assumed wrongly. Bonnie Boo felt every bit of it. She felt trapped too.

One night Mom was bragging to friends over dinner about how Bonnie had spied this nice looking man in the Fred Montesi grocery store. She had caught his eye, smiled at him for a moment and then cried out, "There's a nice Daddy, Mamma! There's a nice Daddy! Can't we please have him for a Daddy?"

Mom and all her friends howled as she went on to describe the terror-stricken look in the poor man's face once he realized that the smiling child was referring to him, and then the look of puzzlement on Bonnie's face as Mom tried to shut her up.

The adults all thought it was so cute …and utterly hilarious. To me it was just one more time when Mom either didn't get it, or simply chose not to. Bonnie wanted, no, needed …desperately to fill some of those many gaps in her little world. Gaps she’d had no part in creating, pain she had no control over. What the hell was so cute and hilarious about that?

Perhaps if I hadn't felt the intensity of those same pangs in my own life for so long, or heard my mother laugh and make fun of my tears and awkward expressions of loss. Perhaps then I wouldn't have been so bothered by her heartless behavior. Sure, I know the story was funny in its own screwed up way and understand that given the choice one can either laugh or cry. That particular evening Mom simply chose to laugh, which honestly didn’t make her a monster so much as it left me feeling hollowed out and mad once again, which, let’s be real, nearly always translates into some achey, bottled up variation on gut-punched sad.

Deep inside, on some almost molecular level I knew my mother hurt like hell too, but that didn’t make her laughter at her baby daughter’s expense feel less clueless or cruel. There were times I know she’d have cried instead of joking, but given the fawning audience and being half drunk, well… I’d seen my mother bent over and gasping for breath often enough to know that tears were no stranger to her cheeks.

Once she had tossed me from the tangled web of her hellish world I was never coming back. I was never again going to submit to her bullying and temper, never again submit as the victim of her malignant sense of tough-shit, ‘Uncle-Calf-rope’ mothering.

Bonnie Boo didn't have another family somewhere safely distant to open up other worlds and possibilities. She was a bastard child in a world where divorce and single mom’s were still taboo, adored and adorable, but also trapped within the prison of her mother’s bastard life, still far too young to understand, still too small to run away. But she felt all of it. Even what she couldn’t yet understand.

Her sad plight and my hatred of the world that held her made me afraid to get too close. I knew without question I was climbing back on a plane at the end of summer, and that I must. I also knew Bonnie would learn soon enough that no one else, not even her big brother could save her from Mom.

I was not as strong as Superman. Neither was I as selfless.

So atop the long list of other things I hated myself for, I added being a cop-out. Some big brother, huh? It took every bit of strength in me to survive and escape the strangling clutches and shame of my mother's world. How could I possibly have enough power to survive that and then win the battle for BonnieBoo as well?

I was only fifteen.

Bonnie was just going to have to find her own way out in time, sort out her own path of survival. That was how I rationalized it to myself while continually adding bricks and mortar to the safe wall I was building between us.

I never counted on what that wall would cost or how long it might stand. I did not consider even once back then that someday I’d have to find a way to forgive myself for chasing my baby sister out of my heart ...then find a way to ask the same of her.

I couldn’t bear to keep growing bigger in my baby sister’s eyes or heart. I didn't want to lead her on, only to utterly fail her later. So I kept that hopeful little, blue-eyed wonder who was constantly begging me to be the hero who would save her …at arms length. I wasn’t nearly big enough take on Mom yet. Bonnie might not have known that but I did. I just couldn't.

And so, on weekends we’d bake cookies and play Candyland, and I’d give her piggyback rides and tickles, safe, chummy stuff like that. But whenever Bonnie got too clingy or adoring I grew strangely cold and distant. Subtle, negative reinforcement. Emotional fucking blackmail. Cowardly self protection.

Immaturity. And fear. I was scared to death to fall for the little shit again, to love her too much, believing it would make things much worse for both of us when I had to leave again. Summers always come to an end.

When Mom had kicked me out a year before it wasn’t Memphis or any of my old friends like Tripp or Boo-Boo Ragsdale, or Danny Schultz I missed most. It was cheerful little Bonnie Boo. More than Mom. More than Cyndi. I didn't want to go through all that again over some bubbly, blue-eyed, little kid.

How could I willingly be the first man in her world to love her and then leave? I knew how it felt to be left behind. My sisters, too. Deep within my gut and bones I still remembered that sickening ache, how heavy and cold it felt. I didn’t want to become that sort of heartache to anyone.

Heroic big brother? Surrogate father figure?

“No way!” my heart insisted. “I don't want that goddamned job!”

“I can’t afford to become that important to anyone yet.”

“I’ll only ditch her.”

“I’ll certainly fail her.”

Self-fulfilling prophecies. Born of loss. Enlarged by fear.

“Cut ties and run like hell!” my heart screamed each weekend I was home in Memphis.

My one safe play was to bail. So that’s what I did.

Damn me.

Damn me straight to hell!

© David E. Perry. All rights reserved.

Told with Bonnie’s permission.

When I was fifteen I lived in a boarding house in Mississippi during the summer and worked, seventy and more hours each week …on a catfish farm where I earned just a dollar an hour. The work was honest, if the circumstances surrounding it were not. My mother was dating the fish farm’s married owner. His wife wrote and signed my paychecks every week. He knew I knew. I knew he knew. I was both liability and oddity, a hard worker trying like hell to be worthy of my paycheck rather than the nuisance brat of some fancy piece of tail.

It was complicated.

Though some chapters of Raisin’ Up Catfish will be only be available to paid subscribers, this one is available free to everyone. If you would like to read others of the more than thirty chapters from this unfolding memoir published thus far, please click on Raisin’ Up Catfish at the top of this page, or in the menu bar at the top of my Substack home page.

Gosh, this made my heart ache for both of you.

"...each of us felt trapped and cheated, again and again by mom's choices." I read your whole chapter, then had to put it away. I actually feel physical pain and a horrible mental malaise reading these passages. I cannot imagine - and I have a pretty good imagination, how it actually felt to be you as a teenage kid, carrying all the burden of responsibility for an irresponsible and largely unresponsive adult. Too young to know anything of alternatives, but with a very strong impulse to cut and run, even if it tore your heart to abandon your sister to the untender mercies of whatever life was going to inflict on her. You had, thank god, a powerful survival instinct, and saving your own life is exactly what you did, because you had to. It was that or let yourself be destroyed. And who would that have helped?

My late husband's first wife was mentally ill, and her psychotic episodes grew worse with time. He was a loving, loyal, immensely caring man, and did all he could for her, but eventually had to admit defeat. As a maritime engineer, he used naval similes and metaphors at times to express his thoughts, and of this situation, he said, 'When you're towing a damaged ship into port, and she begins to sink, there's only one thing you can do: cut the rope. Otherwise, you sink with her." Fitting words for your mother, who was damaged beyond repair and sinking, taking all of you down. You cut the rope. And here you are today - not whole, but with some impressive scar tissue and a heart still beating, a soul still finding and creating beauty. You did the only thing you could. It was the right thing. Your ship sails on.